Intestinal Tumors

What are intestinal tumors?

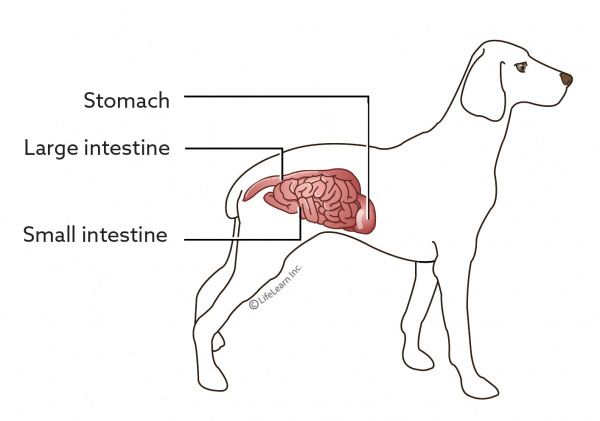

Intestinal tumors develop as a result of the abnormal proliferation and dysregulated replication of cells anywhere along the intestinal tract, which includes the small and large intestines. The small intestine consists of three distinct regions, the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The large intestine also consists of three distinct regions, the cecum, colon, and rectum. Intestinal tumors usually grow from the cells of the inner lining of the intestine or of the muscle that surrounds the lining.

Intestinal tumors may be either benign (non-cancerous) or malignant (cancerous). Malignant tumors are invasive and prone to metastasize (spread to other areas of the body). Most tumors of the intestinal tract are malignant.

In dogs, three types of intestinal tumors are seen: lymphoma, adenocarcinoma, and leiomyosarcoma. While lymphomas tend to occur anywhere along the intestinal tract, adenocarcinomas occur more often in the large intestine, and leiomyosarcomas more often in the small intestine.

In cats, lymphoma is by far the most common intestinal tumor, occurring most often in the small intestine. The next most common is adenocarcinoma, which occurs most often in the large intestine, followed by mast cell tumor and leiomyosarcoma. Other types of intestinal tumors in both cats and dogs include leiomyomas, gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs), plasmacytomas, adenomas, adenomatous polyps, carcinoids, and osteosarcomas. Polyps are more likely to occur in the duodenum (upper small intestine) in cats and the colon or rectum in dogs, and in dogs, they can transform to become cancerous.

While the majority of intestinal tumors in dogs occur in the large intestine, in cats, the majority occur in the small intestine. Overall, digestive tract tumors are uncommon in dogs and cats.

What causes this cancer?

The reason why a particular pet may develop this, or any other tumor or cancer, is not straightforward. Very few tumors and cancers have a single known cause. Most seem to be caused by a complex mix of risk factors, some environmental and some genetic or hereditary. In the case of intestinal tumors, age, sex, and breed appear to be risk factors.

As with many cancers, the incidence of intestinal cancer increases with age. Intestinal tumors tend to occur in middle-aged to older dogs, most often between 6 and 9 years, and older cats, usually between 10 and 12 years. Some tumors, such as leiomyomas, tend to occur in very old dogs (on average, 16 years old). Males are generally at higher risk than females, both for benign and malignant tumors.

Certain breeds are particularly predisposed to developing certain intestinal cancers indicating that that specific genetic predispositions exist. In dogs, leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas (both smooth muscle tumors) tend to occur in the large breeds, most notably German Shepherds. Adenocarcinomas occur mostly in German Shepherds, Collies, Boxers, Doberman Pinschers, Shar-Peis, Poodles, and West Highland White Terriers. Rectal polyps occur more commonly in German Shepherds and Collies. Mast cell tumors are more common in Maltese, as well as other miniature breeds. And tumors of the colon and rectum are more prevalent in Boxers, German Shepherds, Poodles, Great Danes, and Spaniels.

"Certain breeds are particularly predisposed to developing certain intestinal cancers indicating that that specific genetic predispositions exist."

In cats, the Siamese is nearly twice as likely to develop intestinal cancer as other cats, and the incidence of adenocarcinoma is up to 8 times greater than in other breeds. In fact, 70% of small intestinal adenocarcinomas of cats occur in Siamese cats. The Siamese may also be at increased risk of intestinal lymphoma and intestinal polyps.

What are the signs of intestinal tumors?

The signs of intestinal tumors vary depending on the location of the tumor, the extent of the tumor, whether it has metastasized, and the associated consequences.

If your pet has a tumor of the small intestine, you may notice intermittent vomiting, reduced appetite, lethargy, and gradual weight loss. Vomit may be blood-tinged or have a “coffee grounds” appearance. This can occur with tumors of the upper small intestine (e.g., duodenum), that ulcerate (open) causing bleeding. Bleeding from tumors anywhere along the small intestine may cause the stool may become blackish. Chronic bleeding can lead to anemia (low circulating red blood cells) causing paleness of the gums. You may also notice intestinal rumbling or gurgling noises or that your pet is frequently passing gas.

"The signs of intestinal tumors vary depending on the location of the tumor, the extent of the tumor, whether it has metastasized, and the associated consequences."

If your pet has a tumor of the large intestine, you may notice bleeding from the anus, blood in the stool, and a hard time passing stools). Sometimes chronic straining can lead to rectal prolapse (protrusion of the rectal lining through the anus). Sometimes the stools become narrow and ribbon-like in appearance.

When the tumor is located at the juncture of the small and large intestine your pet may have a mixture of signs (i.e., signs of both small and large intestinal tumors). Diarrhea is not common but can occur with tumors of both the small and large intestine. Occasionally the belly can become distended due to fluid build-up in the abdomen.

Pets with intestinal leiomyomas or leiomyosarcomas can develop a lower than normal blood glucose (hypoglycemia). This is a type of paraneoplastic syndrome, a condition when substances released by cancer cells affect the functioning of other organs. Signs of low blood glucose (blood sugar) include restlessness, weakness, trembling, disorientation, and seizures. Another paraneoplastic syndrome with leiomyomas and leiomyosarcomas is tumor-associated nephrogenic diabetes insipidus. This condition causes excessive drinking and urination. Lymphoma and intestinal adenocarcinoma can also cause a paraneoplastic syndrome – hypercalcemia (high blood calcium). Hypercalcemia also causes excessive drinking and urination.

How is this cancer diagnosed?

Your veterinarian may suspect intestinal cancer in an older dog or cat with poor body condition and signs of gastrointestinal upset. The findings with a physical examination are variable. Your veterinarian may find a mass or some distended, painful areas of the small intestine upon palpating (feeling) your pet’s abdomen. The lymph nodes and certain organs (such as the liver) may be enlarged, and the abdomen swollen with fluid. A mass may also be found during a rectal exam.

"The findings with a physical examination are variable."

Your veterinarian will perform tests such as blood tests, urinalysis, imaging, endoscopy, and a biopsy. Bloodwork and urinalysis are helpful to find the changes associated with the paraneoplastic syndromes. Radiographs (X-rays) may show a mass in the abdomen, and specialized imaging (a barium swallow) may show ulceration in the intestine, reduced intestinal movement, or intestinal obstruction. Ultrasound is also helpful, especially to examine the layers of the intestinal wall and to obtain an ultrasound-guided fine needle or core needle biopsy.

This procedure involves taking a small needle with a syringe and suctioning a sample of cells directly from the tumor and placing them on a slide. A veterinary pathologist then examines the slide under a microscope.

Endoscopy, a procedure that uses an endoscope (i.e., a thin tube with a light and tiny camera at the end, and through which forceps can be passed to take tissue samples) can be useful to diagnose the presence of a tumour in most areas of the intestine. It is used to collect biopsy samples as well. As with needle biopsies, these samples are not always valuable for diagnosis and instead a surgical biopsy may be needed to obtain a definitive (accurate) diagnosis. Surgical biopsies may be collected via laparoscopy, a procedure using a laparoscope (a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and lens), or laparotomy (a surgery to open the abdomen). To identify the type of cancer, the biopsies are examined by a veterinary pathologist under the microscope. This is called histopathology. Histopathology is not only helpful to make a diagnosis but can indicate how the tumor is likely to behave.

In the case of rectal tumors, cells can be collected during a rectal exam.

How does this cancer typically progress?

How cancer of the intestines progresses depends on the type of tumor and how it affects the body. Some tumors grow very slowly while others grow quite fast. Without treatment, both benign and malignant tumors will continue to grow, increasingly interfering with intestinal function and risking ulceration or intestinal obstruction. In some cases, ulcerative tumors can lead to perforation of the intestine, with the spillage of intestinal contents into the abdomen leading to a life-threatening infection.

Because most intestinal tumors are malignant, they often metastasize to other areas of the body, including the nearby lymph nodes, liver, and lungs, as well as other organs and the inner lining of the abdomen. With the chance of metastasis, staging (searching for potential spread to other locations in the body) is highly recommended. This may include bloodwork, urinalysis, X-rays of the lungs, and possibly an abdominal ultrasound. Occasionally more advanced imaging is used, such as computed tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). If any lymph nodes are enlarged or feel abnormal, further sampling may be pursued to determine if spread is present.

What are the treatments for this type of tumor?

The treatments for intestinal tumors depend on the type of tumor and extent to which it has grown and spread. With most intestinal tumors, surgery is the treatment of choice.

The surgical removal of tumors that have metastasized is primarily palliative, to ease symptoms and improve quality of life. The long-term outlook in these situations tends to be limited, with surgery providing few months of relief before the metastatic growths become problematic or the tumor regrows. In some cases, surgery can be followed with chemotherapy or radiation therapy. Radiation therapy may be recommended in some cases, such as for adenocarcinomas of the colon.

"With most intestinal tumors, surgery is the treatment of choice."

Intestinal lymphoma in dogs and cats can be localized, growing as a mass in one location, or diffuse, spread out as a general thickening of the intestinal wall. Surgery is advised if it is possible, as it will help alleviate the signs of the cancer, but typically lymphoma is treated with chemotherapy whether or not the tumor is removed. Sometimes chemotherapy is the preferred treatment approach with intestinal lymphoma in dogs and cats. In some cases, radiation therapy may also be recommended.

In the case of muscle tumors, when the tumor is removed, the signs of the paraneoplastic syndrome will resolve.

Is there anything else I should know?

The outlook can vary from excellent to poor, depending on the type of tumor, whether it has spread to other areas of the body, the number of tumors present, and whether all of the cancer can be removed.

Sometimes the prognosis is limited by the degree of debilitation (e.g., weight loss, and malnourishment) or other health conditions your pet has. Your veterinarian or veterinary oncologist will be able to provide guidance on the best plan of care for your pet.